Coming to terms with the messy spectrum of online speech

Who should do the labor — and hold responsibility — for content moderation in the age of Twitter 2.0

Today the governance of online content is more complex than ever: not only the volume of content but its very nature has shifted, from generative AI models that build imagery from photos, to the use of polls to set major policy decisions, including which accounts should be suspended. The laws intended to define the obligations of platforms are largely obsolete and under fire, and even recent efforts in the EU risk becoming quickly irrelevant. With such high stakes, it’s time to revisit the fundamentals of the system: who should be responsible for what content appears on social media platforms, and how should those standards be enforced.

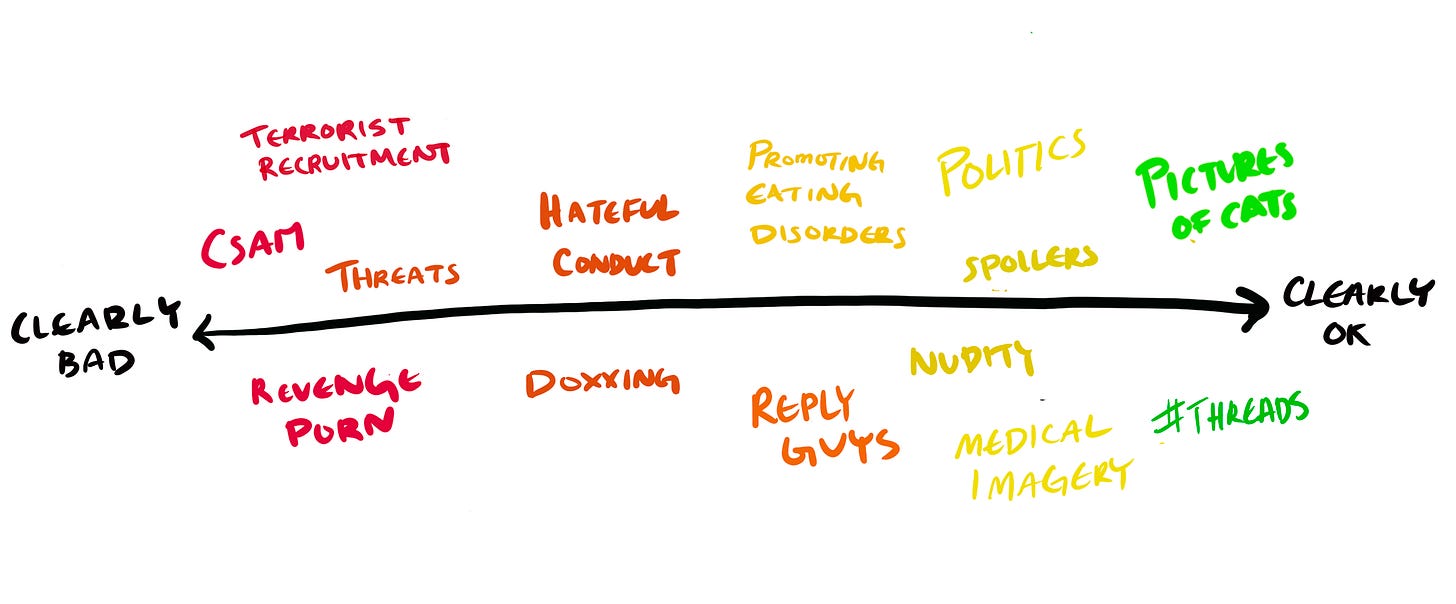

Mapping the messy spectrum of online speech

So what online speech is okay and what isn’t? Platforms have struggled with this question since their inception, and although they would prefer not to moderate at all—can’t everyone just be nice?—in practice they must balance inputs ranging from national laws to prevailing public opinions. The resulting content moderation schemes reflect everything from cultural (lese majeste laws) and historical (neo-Nazi content) norms to service preferences not to show pornography. But to properly examine this question, let’s set aside historical precedent temporarily and define a framework from first principles.

At the risk of oversimplification, I would suggest thinking of online speech as sitting on a spectrum from clearly harmful and indefensible to clearly okay. At one end is what everyone agrees is bad and is already criminalized in current law; at the other is what everyone agrees should absolutely be allowed by all legal and moral arguments.

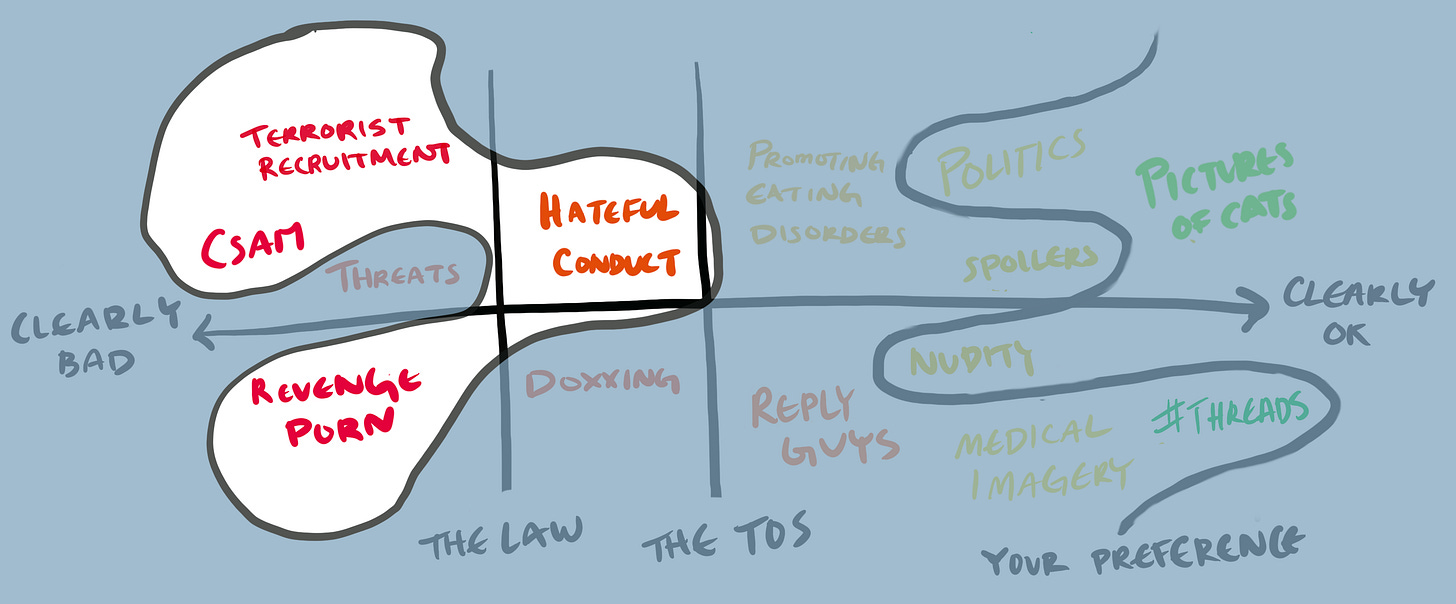

For a given platform, along the spectrum we can delineate a few distinct segments:

Speech that is illegal

Speech that is legal but not allowed in the platform Terms of Service (TOS)

Speech that is legal and allowed on the platform but nevertheless awful and that a user does not want to see

Everything else

The hard part is drawing the lines to define what is permissible by legal, platform, and user standards. Who should be responsible for what? How we uphold our principles should stand the test of time, while the harm and legality of content itself must be allowed to shift and change with social norms (e.g. LGBTQ content).

Here’s an updated functional framework for the division of labor across governments, companies, and individuals:

Policymakers create the bright lines around obvious online and offline harms

Platforms set clear policies around two things:

1) explicitly disallowed content that will lead to a suspension (not only illegal, but also against the TOS) and

2) unwanted/unwelcoming content (the farther right side of the ‘lawful but awful’ category of speech) which will be downranked or have reduced visibility by default

Users decide to opt in and out of those defaults, and can add their own filtering to decide what types of content they do (or don’t) want to see

Of course, setting “clear policies” around any of these lines is not trivial, and will always involve interpretation by the platforms. Questions like what specifically counts as ‘hateful conduct’ will require internal discussion of specific cases, and ideally mechanisms for external review. And regardless of the inherent difficulty of defining some of these policies, there’s growing legal pressure to do just that in some cases, with laws like AB 587 in California requiring platforms to concretely explain, and report on enforcement of, disallowed content policies present in platform Terms of Service.

But at an ecosystem level, focusing on just disallowed content doesn’t go far enough. It’s worth highlighting two ways this functional framework proposes going beyond the current norm in the service of better protecting and empowering users. The first is the suggestion that platforms more explicitly define the default state for content ranking. This is similar to the search ranking guidance that Google offers people who want their content to show up in search. Although Google doesn’t delineate every aspect of the algorithm, in part to protect against attempts to game it, it does give clarity and transparency around not only policy but also mechanisms of enforcement for the legal and TOS lines on the platform.

The second pushes beyond the search ranking analogy to something even more powerful: by making those defaults explicit, platforms—and ideally third party developers—can take the next step to enable users themselves to opt in or out of the default state, and add their own filtering to further control the content they see. This shift gives as much power to enforce boundaries to users as possible.

The challenge of enforcement

Of course, none of this matters if standards aren’t enforced effectively or proportionately. If lawmakers fail to put pressure on platforms to do their jobs, what’s the point in having the law? And if platforms are too lax, that’s tantamount to not having ToS in place at all. One example is some of the neo-Nazis who were recently allowed back on Twitter despite numerous instances of policy violations in the past.

On the flip side, platforms have also enforced their terms in ways that are disproportionate to the problem and/or give too much power to those in positions of authority. Recently, Elon Musk came under fire for suspending journalists for alleged violations of a new doxxing policy. Given the tenuous justification for the suspensions, many read the situation as the platform owner trying to clamp down on accounts that were critical of him, and the results of his own polls recommended reinstating them.

So on one hand, we have potential under-moderation by the platform and on the other, over-moderation. What role should policymakers play in attempting to correct these issues? Given the urgency of the problem and the nature of democracy being a slower and more deliberative process (for good reason; there needs to be caution and awareness of the externalities of overregulation!) I’d suggest that while policymakers determine categories of harm, we need to put more pressure on the platforms to give users more control over how we enforce our own preferences, in line with the framework suggested above.

This balances the power between governments, platforms, and most importantly users, in a way that has not been possible before. Instead of giving more authority to platforms, it creates space for the democratic process to work at the policy level, while giving individuals the ability to curate what works for them. We can’t rely on Musk, Zuckerberg, or even platform safety teams to reflect our preferences for standard development or enforcement. To date, that’s only created either more aggressive and creatively interpreted enforcement actions that many users find objectionable, or lax enforcement that has resulted in overexposure of violence, nudity, or hateful conduct in ways that are out of line with cultural expectations.

Empowering us

If we circle back to our framework, now in the context of the real challenges of enforcement and platform regulation, one clear opportunity emerges to improve the system: empowering users to define and enforce their own needs. Although we might expect platforms to enable this behavior of their own accord, all recent signs imply otherwise. In the meantime, if policymakers and end users better understand the key lines the platforms must draw, we all can push for change in more practical ways.

Instead of vaguely demanding “better” from the platforms when they see content they don’t like, users can ask: Where on the spectrum does this content fall? Am I seeing it as a result of poor platform interpretation or enforcement of the legal or TOS line? Or is it more likely just outside my personal preferences? And if the latter, why don't I have the tools to avoid seeing it in the first place?

And in turn, policymakers can avoid trying to nudge platform TOS requirements via new legislation, and instead require platforms to make it not only possible, but easy, for users to make these choices for themselves—by opening up their APIs. Because when it comes to the messy middle of the content spectrum, policymakers should focus less on precisely where the platform draws its line, and more on how to ensure users can draw their own.